A veteran of the hip-hop scene and internationally celebrated breakdancer, Nancy Yu – AKA Asia One – has her justifiable share of individuals contacting her on the lookout for recommendation. However the message she acquired in 2019 from a younger Afghan was a little bit totally different.

Pissed off by his breakdancing crew’s incapacity to get visas to carry out internationally, Moshtagh* was questioning if Asia may assist. “He felt they had been actually good, however they felt, like, invisible to the world,” she says. “I favored him. He wasn’t attempting to bug me or say ‘we’d like this proper now’ … He appeared fairly humble and trustworthy.”

Over the months, a friendship grew between Kabul and California, primarily based on mutual respect and an appreciation of hip-hop tradition. Moshtagh, who’s in his 20s, felt he had loads to be taught from Asia, a one-time member of the Rock Regular Crew who arrange the B-Boy summit, a worldwide gathering celebrating all the weather of hip-hop: breakdancing, DJ-ing, rapping and graffiti.

Solely as soon as has her perception in Moshtagh’s humility been severely challenged: when he declared, with youthful bravado, that he might be higher than Tupac Shakur. “I used to be, like, ‘you’re out of your thoughts’,” Asia laughs.

Final 12 months, because the Taliban made sweeping positive aspects throughout Afghanistan and even the modest freedoms loved by many younger folks in Kabul began to really feel doubtful, Moshtagh’s messages turned extra severe and pressing. And in the summertime, because the Taliban took the capital, got here the choice: the hip-hoppers, he informed Asia, had been leaving.

It was a call “primarily based on full worry”, says Asia. “You realize, simply that overwhelming sense of survival, that ‘if we don’t depart now, we don’t know what’s going to occur to us. And so we’re gonna threat our likelihood’. As a result of … they felt so threatened by the Taliban primarily based on their western practices.”

Now Moshtagh was asking his American mentor for various assist: “He mentioned, I really feel such as you guys have an obligation to assist us and I used to be like, what do you imply?” she remembers. “And he mentioned, properly, , we’re all simply hip-hop household. And … the increasingly we spoke, the increasingly I realised that a lot of what he was saying was true.”

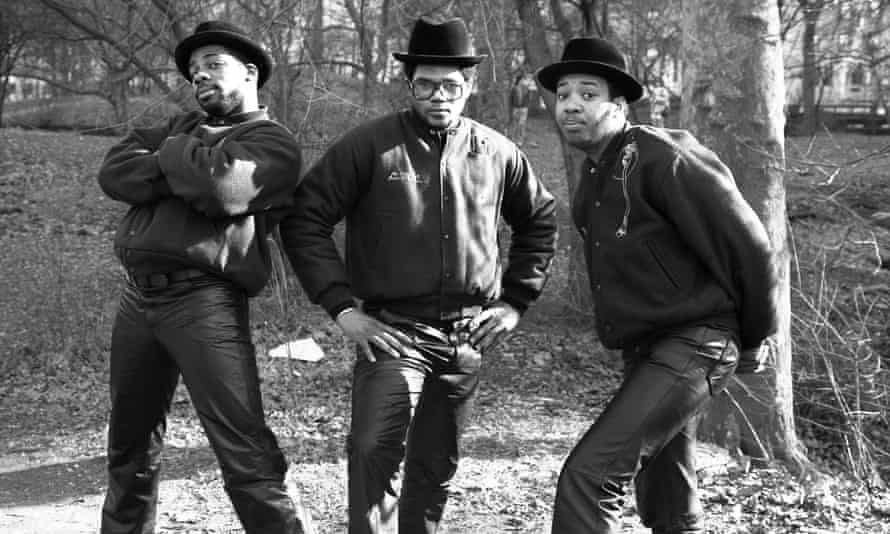

Ever since hip-hop first erupted within the Bronx house blocks of Nineteen Seventies New York, its social conscience has by no means been distant. From the day by day struggles of black America to the battle on medication to police brutality, there may be little about life on the margins that hasn’t been rapped, sprayed on partitions, chanted at rallies. (Throughout the summer season of 2020, it was a 1989 Public Enemy anthem that echoed at lots of the protests over George Floyd’s homicide. “Gotta give us what we would like./ Gotta give us what we’d like./… We’ve gotta struggle the powers that be.”)

Within the period of billionaire rappers and ostentatious bling, it may be simple for that activist spirit to get misplaced. However for Asia, who heads No Straightforward Props, a nonprofit operating hip-hop occasions and courses for marginalised communities in Los Angeles, it’s intrinsic to the scene and partly why she felt touched by Moshtagh. “It awoke my thought course of. Listed below are some folks that really feel invisible. And hip-hop was began by a bunch of folks that felt invisible,” she says. “To me, not having the ability to practise hip-hop is one factor, and never having the ability to stay is one other factor,” she says. Inside days of his request for assist, she began to mobilise.

Moshtagh is a mild-mannered man in his 20s whose spoken English is closely flavoured by hip-hop. He speaks of “homies,” of “breakers”, of “B-girls” and “B-boys”. As a young person in Hamid Karzai’s Afghanistan, he fell for the strikes he noticed in movies of breakdancers from distant, and set about attempting to grow to be similar to them – maybe even higher.

In a rustic that retained a deep social conservatism lengthy after the Taliban had been toppled in 2001, it was not a simple path.

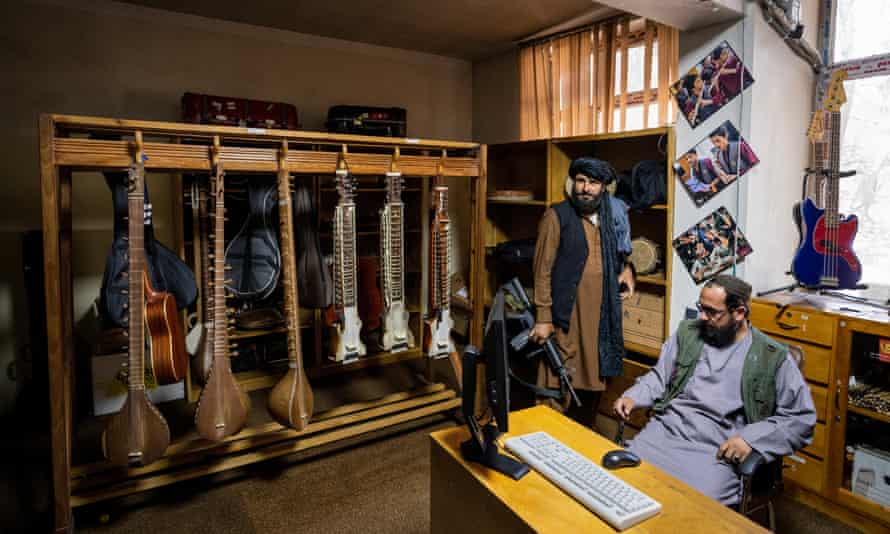

“Folks didn’t settle for hip-hop,” says Moshtagh. “They had been simply pondering that this has music: ‘it’s haram, you may’t do it, it’s unlawful. What is that this western tradition that you just guys are selling?’ However we had been simply pondering we’re trendy folks; younger folks must search for trendy issues, and we love to do that.”

Regardless of disapproval and threats, he and his mates made progress. “We modified folks in 10 years however all the things fell aside,” he says. “That constructing that we constructed, really, it’s destroyed. There’s nothing for us to do in Afghanistan any extra.”

On 18 August, three days after the Taliban overthrew Ashraf Ghani’s authorities, Moshtagh left Afghanistan, together with a few of his “homies”. They’ve been in a neighbouring nation ever since, attempting to stay hopeful butconstantly worrying concerning the future.

“Truly, we don’t care about ourselves that a lot,” says Moshtagh, through Zoom, his five-year-old sister coming up and down within the background. “We’re simply enthusiastic about our relations. We don’t need them to be in a tough state of affairs due to us, due to what we had been doing. It’s all on our shoulders.”

Based on Menno van Gorp, a Dutch breakdancer with greater than 100,000 Instagram followers who has been in contact with him for years, Moshtagh “is a man that carries a number of duty for the folks round him … He’s the one which retains the wheel spinning.”

Alongside Moshtagh, there are 19 within the group, together with two youngsters and 6 ladies. A mix of breakdancers, rap artists, parkourists and relations, they really feel there is no such thing as a place for them in Afghanistan at present. “I’m positive they [the Taliban] wouldn’t settle for it. There’s no area [for it],” he says. Among the group have brazenly criticised the Taliban. Including to the group’s worry is their ethnic background: all however three are Hazara, essentially the most discriminated in opposition to minority group within the nation.

For one of many dancers there may be the extra complication of being a lady. Earlier than leaving Kabul, Haleema* had been hoping to compete within the 2024 Olympics – the primary to have breakdancing as an official sport. When she first noticed movies of individuals doing it she thought it have to be “a sort of Photoshop” however she skilled arduous, and acquired threats to her life for doing so.

However she knew she couldn’t proceed underneath the Taliban: the group have made their opposition to feminine sport clear, and breaking has the extra stigma of additionally being a type of dance. So inextricably linked is Haleema’s life to hip-hop, she, too, determined to go away. She insists it was not a troublesome choice. “I’m very younger,” she says. “At my age, there is no such thing as a inconceivable.”

Van Gorp says that for years, amid continual nationwide instability, hip-hop gave Moshtagh and the others sanctuary. “Breaking was the factor that saved them sane,” he says. “Like, they name it ‘hip-hope’ as an alternative of hip-hop.”

Even now, in limbo, unable to exit, Haleema nonetheless desires of competing within the Olympics. “I’m simply looking for a technique to get out, and to coach,” she says. “I’ve acquired hope for the long run due to the folks which can be serving to us.”

By final autumn, Asia One had constructed up a small however devoted crew for the #SaveAfghanHiphoppers mission. “Hip-hop tradition is about giving again, so let’s assist our neighborhood members in want,” reads the marketing campaign web site.

They raised practically $14,000 (£10,000) to cowl the group’s primary wants corresponding to meals, clothes and shelter, in addition to preliminary authorized prices. However time is ticking on, and the prices are prone to mount, so the marketing campaign is eager for folks to donate.

Practically six months after they fled, the group continues to be hoping to be granted passage to a rustic that can give them asylum. For now, the hip-hoppers, many with out passports, stay in hiding lest they’re arrested and deported again to Afghanistan.

“If we increase $50,000, we will get them out of there,” says Asia. “We predict it’s really very potential.”

The mission’s lawyer, Jaclyn Fortini Laing, is working to discover a nation keen to take the hip-hoppers. The US and the UK, each key to Afghanistan’s latest historical past and international hip-hop tradition, have proved useless ends.

That’s a disgrace for the group and the international locations in query, says Fortini Laing. “The beliefs that [the hip-hoppers] stand for – freedom of speech, ladies’s rights – are the beliefs that make them a goal for the Taliban however would make them an asset to some other nation that was keen to take them in,” she says.

“Failure,” she says, “just isn’t an choice.”

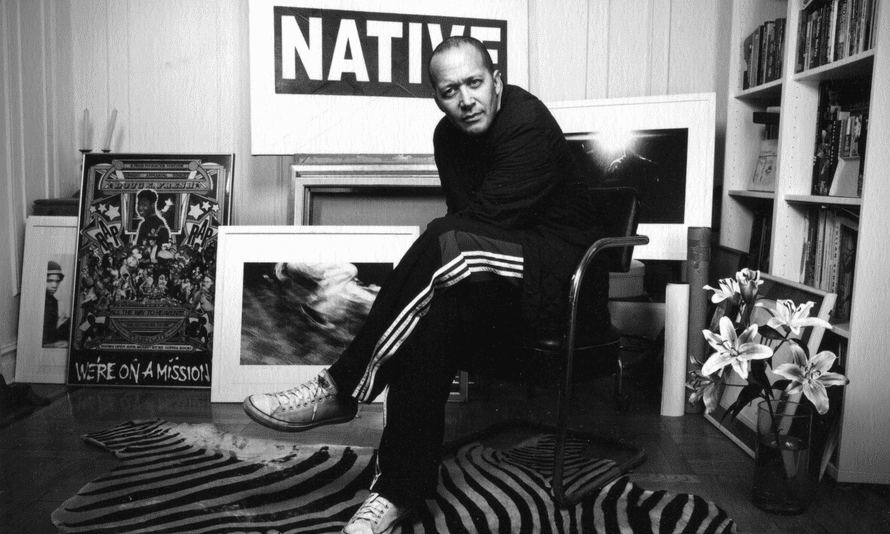

Equally decided for the mission to succeed is Michael Holman, a pioneer of hip-hop’s first wave who has gone on to have an eclectic profession as a Broadway producer, film-maker and musician. When Asia rang round to see who may be keen to assist the Afghans, he was one of many few who mentioned sure.

“I used to be like, I can’t say no,” he says.

Holman, 66, is believed to be the primary author to have used the phrase “hip-hop” in print: in a 1982 interview with Common Zulu Nation’s DJ Afrika Bambaataa for the East Village Eye, he defines “the all-inclusive tag for the rapping, breaking, graffiti, crew style carrying avenue sub-culture”. (Elsewhere within the article he rhapsodises about a night at the Ritz the place Zulu Nation “threw down” a Rolling Stones monitor: “Honky Tonk Girl by no means rocked so arduous!”)

Closely concerned within the early days of hip-hop when the likes of Grandmaster Flash and the Beastie Boys had been rising, Holman helped introduce the “park-jam tradition” that had emerged uptown to downtown Manhattan, after which to the world. In 1981, he took Malcolm McLaren to the Bronx to see what all of the fuss was about and, “blown away”, the previous Intercourse Pistols’ supervisor requested him to place collectively a present that includes Jazzy Jay and Rock Regular Crew.

Holman constructed an intensive archive of video footage, partly from his short-lived TV present, Graffiti Rock; movies from the daybreak of hip-hop that went everywhere in the world. “[They] had been horrible copies,” he says. “However these tapes had been how these dancers learn to dance world wide.”

So he felt duty-bound to assist. “I felt I owed them one thing,” he says. “I used to be a mentor, in a method, by spreading this tradition, and so they embraced it as a result of I and different folks like me made it a compelling, thrilling and plain cultural factor. I now owed them one thing. I had a duty not solely as a hip-hop pioneer and impresario however I now owed them one thing as an American.”

Moshtagh has many questions for the US, broadly criticised for its rushed, chaotic departure from Afghanistan. Questions, too, for the UK, which supported its 20-year mission. “Your international locations got here to Afghanistan to convey peace; you spent some huge cash … And now you left these folks alone. Why don’t you care about them?” he asks.

He doesn’t know the place he’ll find yourself. Spain or Belgium seem the most probably candidates, however the course of is slowed down in diplomatic negotiations. Van Gorp, in Rotterdam, is optimistic that, wherever they go, there shall be a neighborhood ready-made for them.

“Breaking is such an excellent bridge to attach with native folks as a result of it’s so open and welcoming,” he says. “It’s going to actually assist them settle. So, like, wherever they may go there shall be B-boys they will join with and they’ll have already got a small community.”

Moshtagh doesn’t know if he’ll see Afghanistan once more. He needs to be in a protected place. “It doesn’t matter [where]. This Earth is my residence. Earth is for human beings,” he says. Haleema simply needs the agonising uncertainty to finish. “[In] actual life, you’re free to do all of the issues that you really want,” she says, merely. “I need to stay free.”

* Names have been modified

Join a distinct view with our International Dispatch publication – a roundup of our high tales from world wide, really helpful reads, and ideas from our crew on key improvement and human rights points, delivered to your inbox each two weeks:

Join International Dispatch – please test your spam folder for the affirmation electronic mail